The Art of Maurice Sendak

Listen to the Recess! Clip

| Author | John Cech |

| Air Date | 6/10/2004 |

Art of Maurice Sendak Transcript

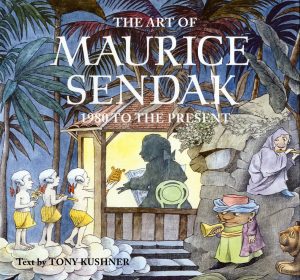

It’s Maurice Sendak’s birthday today, and the award-winning playright Tony Kushner, Sendak’s friend and collaborator (on the recent picture book, Brundibar), has offered a remarkable present for the occasion: The Art of Maurice Sendak, 1980 to the Present. This large, beautifully produced volume is a kind of sequel to Selma Lanes’ 1980 book which has the same title and publisher. But Kushner’s approach is very different: his probing, personal portrait of the artist is one the first to use Sendak’s own diaries and journal entries, as well as years of Kushner’s memories of Sendak, based on their friendship. Happily, it is filled with illustrations from many of the children’s books that Sendak has done over the past twenty-some years, since Lanes’ book appeared, like Outside Over There, Dear Mili, and We’re All in the Dumps With Jack and Guy. And Kushner looks at the origins of other books that have received relatively little, critical attention, like the many pictures Sendak provided for Iona Opie’s unique collection of children’s nursery rhymes, I Saw Esau, and the powerful suite of illustrations he did for Herman Melville’s Pierre.

Given Kushner’s own interests, it isn’t surprising the insight he brings to Sendak’s parallel career as a writer and designer for the stage, through several dozen operas, musicals, and indescribable entertainments — like the short plays he has created for the Night Kitchen Theater over the past decade. There are lush spreads of Sendak’s amazing designs for stagings of his own works, as well as for Tchaikovsky’s ballet, The Nutcracker, for Mozart operas like The Magic Flute, and for Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, Janacek’s The Cunning Little Vixen and Ravel’s L’Enfant et les Sortileges. Kushner takes us right up to the present, with Sendak’s set designs for the operatic version of Brundibar, which was performed in Chicago last winter — the first time that short opera has been heard since it was staged by children in the Nazi’s Terezin concentration camp during the 1940s.

Sendak turns 76 today, a kind of gregarious hermit, who loves both solitude and company, “who feels ferociously, ” Kushner reminds us — especially for the plight of children. “Maurice, among the best of the best,” Kushner writes, “shocks deeply, touching on the mortal, the insupportably sad or unjust. . . . He pitches children, even aged children, out of the familiar and into mystery, and then into understanding, wisdom even. He pitches children through fantasy into human adulthood, that rare, hard-won and let’s face it, tragic condition” (197-8). At the end of his essay, Kushner describes Sendak’s face, reading the expressions that are registered in its contours, finding in Sendak’s eyebrows, arched in surprise, one of the keys to understanding what Sendak brings to his work, his view of the world, and to his life: “an astonished heart.”