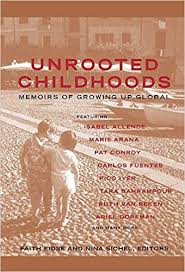

Unrooted Childhoods; Memories of Growing Up Global

Listen to the Recess! Clip

| Author | John Cech |

| Air Date | 5/10/2004 |

Unrooted Childhoods Transcript

In their recent book, Unrooted Childhoods, Faith Eidse and Nina Sichel have collected a series of memoires about what they call “Growing Up Global.” Eidse and Sichel were inspired to gather this collection when they discovered — in trying to find books to help explain to their own children and students that sense of not fully belonging in any one place — that such a group of recollections from people with similar experiences did not exist.

Eidse had grown up in the Congo/Zaire, and Sichel was raised in Venezuela. Both women felt a strong, pervasive, highly personal connection to these places of their childhood long after they had left them; they were, to use David Pollock’s term, Third Culture Kids. Eidse and Sichel describe these kids in their introduction: “They are perpetual outsiders, millions of children around the world, born in one nation, raised in others, flung into global jet streams by their parents’ career choices and consequent mobility….Their parents are educators, international businesspeople, foreign service attaches, missionaries, military personnel. The children shuttle back and forth between nations, languages, cultures, and loyalties….They belong everywhere and nowhere…” (1-2).

Some of the voices in this book will be familiar to American audiences, like that of Isabel Allende, who contributes an essay about her childhood journey from Chile to Bolivia and finally to Lebanon, where she first read A Thousand and One Nights, hidden inside a wardrobe cabinet and discovered a fictional world with “food, landscapes, palaces, markets, smells, tastes, and textures [that] were so rich that after them the world has never been the same to me” (78).

The son of a Marine Corps pilot, Pat Conroy writes about growing up as “a military brat,” part of an “undiscovered nation.” He writes: “The military brats of America are an invisible, unorganized tribe, a federation of brothers and sisters bound by common experience, by our uniformed fathers, by the movement of families being rotated through the American mainland and to military posts in foreign lands” (107).

This remarkable, moving book and its nineteen recollections will take you to faraway places of the earth, of memory, and of the heart. “I yearn,” Faith Eidse writes, “for thick gumbo-limbo roots but recognize myself as the mangrove, whose vine and root are one. I simultaneously branch and root as I go, more devoted to freedom than to permanence” (142).