Labor Day and Lewis Hine

Listen to the Recess! Clip

| Author | John Cech |

| Air Date | 9/2/2002 |

Labor Day and Lewis Hine Transcript

Early in the 20th century, one of the more dangerous artistic careers was photographing the working conditions of American children, in our factories and mines, on the streets and in the packing plants. And no one took more chances in pursuit of his vision — for a safer, kinder world for children and more respect for working people in general than the extraordinary documentary photographer, Lewis Hine.

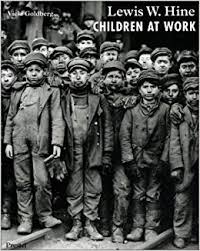

A book of Hine’s photographs of children, Lewis W. Hine: Children at Work from Prestel publishers, collects nearly 100 of Hine’s remarkable portraits of young people caught in the crush of Robber Baron American, decades before America finally passed its child labor laws. In these phots we see boys in 1910 Pennsylvania, blackened with coal dust, bent over the breaker chutes for 12 to 14 hours a day, their mangled hands pulling the slag and stones from the quick stream of coal that passes beneath their feet, losing their childhoods and their health for less than five dollars a week. And here are girls so small they had to stand on boxes to run the knitting machines in a hosiery mill, so small they had to climb onto the spinning looms to straighten a thread — a move that might cost them a finger.

In the first two decades of this century, Hine worked for the National Child Labor Committee. “I have followed the procession of child workers,” he wrote,” winding through a thousand industrial communities, from the canneries of Maine to the fields of Texas. I have heard their tragic stories, watched their cramped lives and seen their fruitless struggles in the industrial game where the odds are all against them.” Hine risked beatings, and worse, to take his pictures and case histories. He would seek out the children, and have quiet conversations with them, recording their bleak lives in his notebooks, but Hine’s ceaseless efforts led to some or our earliest national legislation concerning child labor. Hine died in 1940, at the age of 66, all but forgotten as an artist. No one seemed to care about those miraculous portraits of immigrants that he took at Ellis Island, or even the breath-taking, now classic photographs that he did of the construction of the Empire State Building. In the end, he was consigned to the same poverty that he had recorded among the working children, women, and men of this country. But Hine didn’t complain. A true artist, he devoted his life to bearing witness. And he turned the haunted facts of these children’s lives into transcendent poetry. Look at these faces, and you’ll see it written, movingly, achingly there.