George Herriman and Krazy Kat

Listen to the Recess! Clip

| Author | Laurie Taylor |

| Air Date | 8/22/2002 |

George Herriman Transcript

The whimsical music you’re hearing is from John Alden Carpenter’s ballet “Krazy Kat,” that was inspired by George Herriman’s comic strip, Krazy Kat, which first appeared in 1913. Herriman’s graphic and verbal dance, for decades across the pages of the Hearst newspapers, had a pervasive influence on those who created comics and animated cartoons, from Walt Disney and Walt Kelly, to such recent masters of the comic strip as Peanuts’ Charles Schultz and Calvin and Hobbes’ Bill Watterson.

George Herriman began writing “Krazy Kat” when full page comics were the norm for newspapers trying to gain new readers. Comics were one of the ways to build that loyal customer base, and so gifted artists like Herriman were given the space each week to produce free-flowing, witty, beautiful works of art which would appeal to young and older readers alike.

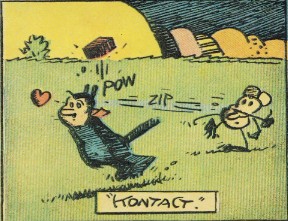

The comic strip itself focused on the strange, often plotless adventures of three main characters: the dreamy optimist, Krazy Kat, who is oblivious to life’s perils; the brick-throwing realist, Ignatz the mouse, who is infuriated by Krazy’s spaciness; and the voice of authority, Officer Pupp, the dog policeman — who is forever trying to protect Krazy from Ignatz’s outbursts by locking the mouse up in the hoosegow. Visually, Krazy Kat’s characters were simply drawn, more like a child’s sketches than carefully finished pictures; and they lived and played on expansive surrealistic landscapes with polka dot hills, green skies, and purple mesas.

From this unusual assortment of elements, Herriman crafted seemingly inexhaustible variations on a basic theme: that experience will forever be knocking innocence over the head, while official efforts struggle to prevent it. In many ways, Krazy Kat’s simple, and at the same time complex premise would provide a pattern for many later comic strip and cartoon situations — like Wile E. Coyote endless pursuit of the Roadrunner or Bugs Bunny’s regular tricking of Elmer Fudd. But Herriman’s remarkable genius enabled him to communicate this truth through a blending of sophisticated comic poetry and avant-garde graphics in that most egalitarian of places, the funny papers — where young readers could enjoy high art over breakfast, and where Presidents like Woodrow Wilson, who was a devoted fan and often quoted Krazy Kat, could give the lowly comic a place in his cabinet.

Explore This Topic Further

Books

[supsystic-gallery id=9]Film

View George Herriman’s 1916 short “Krazy Kat Goes a Wooing”

Further Reading