Winsor McCay and His Fantastic Little Nemo

Listen to the Recess! Clip

| Author | John Cech |

| Air Date | 5/5/2004 |

Winsor McCay Transcript

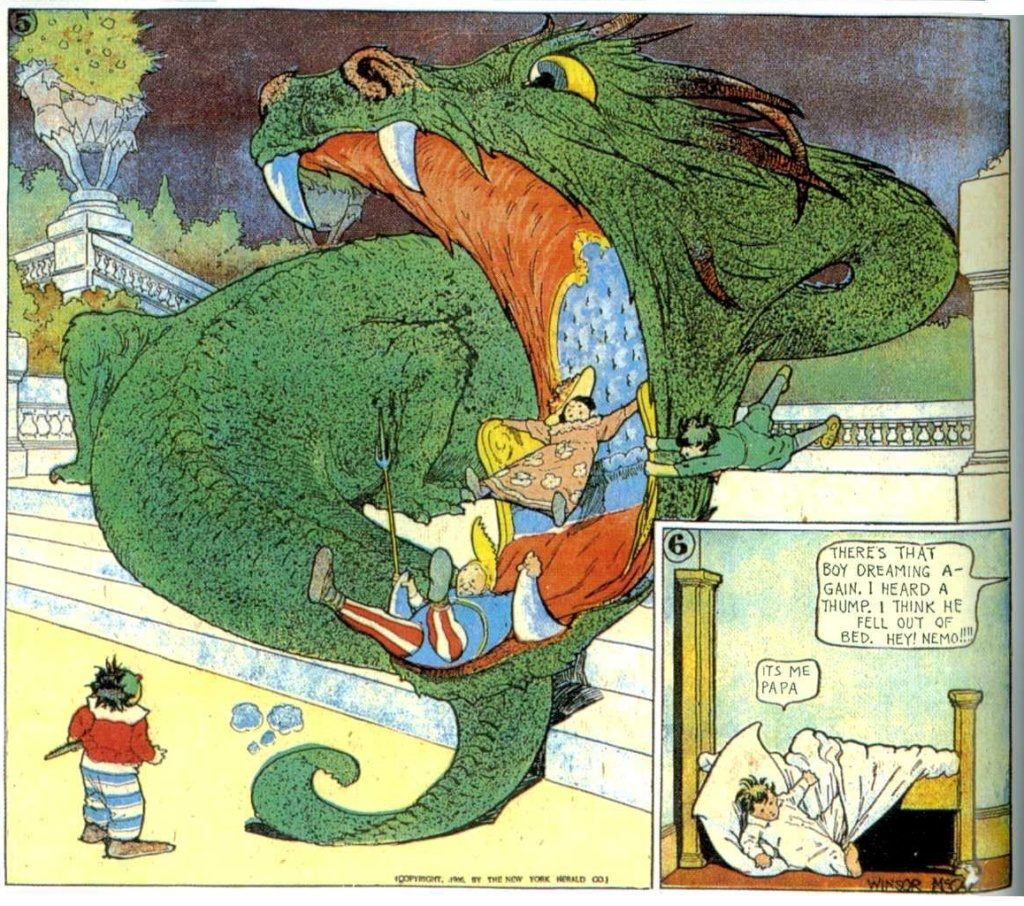

It’s Cartoon Art Appreciation Week, and the place to begin any reflections on the history of this most popular and unappreciated art form is with Winsor McCay. For several decades at the beginning of the twentieth century, McCay was one of America’s best-known artists. During these years, he produced an astounding series of comic strips, starting in 1904 with “Little Sammy Sneeze” which was about an innocent boy with a big Buster Brown collar who has the power to bring any checkers game or parade — or, for that matter, any human activity — to a catastrophic end every time he sneezes. Later that same year, McCay gave his fans the “Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend,” about a man who eats Welsh Rarebit, that nightmare-inducing concoction of toast and melted cheese, before going to bed and then has some of western civilization’s most disturbing dreams. And then, in 1905, McCay brought us “Little Nemo in Slumberland,” one of the masterpieces of American comic strip art — indeed, one of the masterpieces of American Art, period.

In the weekly adventures of Little Nemo, about a little boy’s astonishing fantasies, McCay broke all the rules about how a comic strip should look. He reconfigured the regular panels of the full page strip into amazing geometries, adding optical illusions, and placing the whole into a package of color and design that have influenced generations of artists, including the Surrealists, Maurice Sendak, and the singer Tom Petty. And this on a piece of paper that might well be used the next day to wrap fish. Each episode followed Nemo on one of his nocturnal adventures — flying in an airship to Mars; or galloping through the streets of a city on his bed, which has grown gigantic, rubbery legs; or being chased by a red giant; or miraculously saving the city’s poor children with the sudden powers that are bestowed on him in his dream. At the end of each strip, Nemo winds up back in his own bed, tousled, breathless, bewildered — but truly, deeply dazzled — and us with him.

If McCay had only done the “Little Nemo” comic, it would have been enough. But, ever restless he went on to become one of the principal innovators of the animated film, which led in 1914 to his incomparable short movie Gertie the Dinosaur, which he toured as part of a vaudeville act. By the 1930s, McCay was essentially forgotten. Only Walt Disney acknowledged how much he owed to McCay’s genius. “All of this,” Disney reportedly told McCay’s son, Robert, referring to the burgeoning Disney studios of the 1940s, “should be your father’s.” One can only dream about the theme park McCay’s comics would have made.

Explore This Topic Further

Books

[supsystic-gallery id=7]

Film

View Winsor McCay’s 1911 hand drawn animation “Little Nemo.”

Further Reading