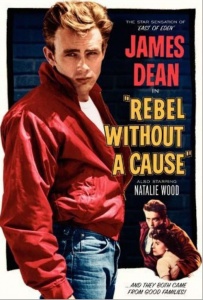

Rebel Without a Cause

Listen to the Recess! Clip

| Author | John Cech |

| Air Date | 10/27/2000 |

Rebel Without a Cause Transcript

It begins with a siren wailing, which is joined by another wail, a teenager’s drunken imitation of the siren that soon becomes a cry for help. It’s the anniversary this month of the premier, in 1955, of one of the definitive movies about the adolescent experience, Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without A Cause. The film launched the adult acting career of Natalie Wood and introduced then unknown Sal Mineo; but it made James Dean a star, a cult figure, and the avatar of every teenager questing for an authentic identity, which is to say, every teenager.

The story, as critics have frequently pointed out, is part “Romeo and Juliet,” part coming-of-age allegory, part sociological study of troubled youth. In fact, the inspiration for Rebel Without a Cause was drawn from the real case study of a violent teenager. “Rebel” appeared at a time in America when teenagers were no longer being seen publicly as the cheerful tap dancers of the Andy Hardy movies. Sociologists and psychologists were scrambling to explain what was regarded as an increasingly rebellious, alarmingly alienated, violent, and sexualized generation of young people. Permissiveness, affluence, movies and comic books, and the beginnings of Rock and Roll were singly or collectively blamed for the drift of teens away from the traditional, sheltering restraints of the family. In The Wild One, that other famous rebel movie from the Fifties which appeared the year before Rebel Without a Cause, Marlon Brando’s biker character is asked, “What are you rebelling against?” To which he replies, “What have you got?”

But Rebel Without a Cause is less open-ended, despite its title. Jim Stark, the protagonist is the new (and, ultimately, good) kid in town. But he’s goaded — into , first, a knife fight and, later, into the now archetypal “chickie run” in stolen cars — by a gang of kids whom he both admires and wants to join and at the same time rejects. He’s looking for direction in his life, and he can’t locate it in his stereotypically nagging mother and carping grandmother, and he certainly can’t find it in his father, played by Jim Backus (of “Mr. Magoo” fame), who is reduced to wearing lace-trimmed aprons around the house, a heavy-handed sign of his empty-handed authority.

So Jim looks to his new friends — Judy and Plato, who both have their own deep troubles at home, and the three start a new family among themselves. As we know, this is exactly what teenagers do — the film really gets that right, and, with it, that aching need to belong, to be forgiven mistakes, to be honestly and patiently guided, to be loved, to be accepted. That, of course, is the cause.