Keep the Books, Even Though They’re Movies

Listen to the Recess! Clip

| Author | John Cech |

| Air Date | 11/16/2004 |

Keep the Books, Even Though They’re Movies Transcript

One of the joys of reading any book, especially when we’re children, is that we can imagine how Charlotte the spider speaks, what aromas are filling Middle Earth, the slant of light in Wonderland, or which way the wind blows in Oz. Even if the book has pictures, we, the readers, get to fill in all those sensory gaps between the pictures and often within the pictures themselves. What does Piglet really look like? We only have a few of E. H. Shepard’s lines to tell us. And it’s enough: we naturally and surely add the crucial details — we actively participate. Aladdin’s magic carpet has twining leaves and vines in our version, the genie speaks slowly, the wishes aren’t sight gags. But once there’s been a movie made of a cherished work of childhood, everything changes: The Cat in the Hat will always have a little of that Mike Meyers vibe to him, the grandfather in The Never-Ending Story will always sound gravely like Peter Falk, Tinker Bell will always look like Julia Roberts. Film and other visual forms are such powerful, all-encompassing media that they seem to trump everything else, especially books.

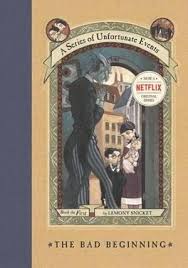

I feel like some kind of Luddite of the imagination saying this, but I almost wish that no book for children could be changed into a movie, until at least several generations of kids have had a chance to read and savor the book first. That way, when the 3-D animation of Chris Van Allsburg’s The Polar Express hits the metroplexes this month, it wouldn’t lead kids who see the movie first to disqualify the book because it lacks the motion of the picture. That way, when Jim Carrey appears in the first film based on Lemony Snicket’s series of Unfortunate Events, a child reader won’t claim that he looks the only way that Uncle Olaf could possibly look. That way, when the greatest book about wizards for young people, Ursula LeGuinn’s Earthsea Trilogy, moves onto the small screen as a mini-series in December, we won’t confuse it with the original.

Creators of children’s books, artists and writers alike, are being pressured by their publishers, their agents, their families, and themselves to exploit their brand names, if they’re lucky enough to have them, and maximize their earning potentials. But what this has led to, almost without exception, are films that are always at least a few steps behind the book, and often miles. So please, please, please — this holiday season: if you’re going to a movie based on a children’s book, be sure that your kids have read the book first, preferably several times. And remind them as you go into that darkened hall, that this isn’t really Dr. Seuss. He, dear ones, can only be found in a book.