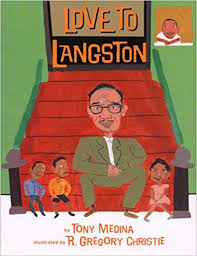

Love to Langston

Listen to the Recess! Clip

| Author | John Cech |

| Air Date | 2/1/2005 |

Love to Langston Transcript

It’s the beginning of Black History Month, and it’s also the birthday of one of America’s best-known African American poets, Langston Hughes, who was born in 1902. He’s the subject of a recent biography for young people, Love to Langston, by Tony Medina, with illustrations by R. Gregory Christie. What’s so unusual about this book, and so right about it, is that it tells the story of Hughes’ life through the poems that Medina writes about that life, beginning with the loneliness of Hughes’ childhood, that’s evoked in Medina’s first poem in the book, “Little Boy Blues.” Medina is referring here to the biographical fact that Hughes spent a good part of his childhood living with his elderly grandmother, Mary Langston, in Lawrence, Kansas. Because of the white children in the neighborhood, who threatened Hughes, she refused to let him leave the house or yard. Instead, Ms. Langston told him stories, and Medina places us there, with young Langston, listening to her:

Of how she is African, French and Cherokee

and how they tried to kidnap her into slavery

Grandma tells me her stories wrapped in her shawl

that has its own story with its bloodstains and

bullet holes and all from her husband who

was killed with John Brown at Harper’s Ferry . . . .

Through the poems, we grow up with Langston, move with him into school and his first protest against segregation, in an America that had only begun in his lifetime to find its way past racism. For Hughes, his refuge was the library and its books, then after high school and a year at Columbia in New York City studying to be an engineer, it was poetry. And poetry soon led him as a young man to Africa. He worked his way there on a steamer and en route, he literally through all his books overboard, vowing to continue his education through travel and first-hand experience. The only book he kept, Medina tells us, was Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

Love to Langston feels like a series of songs, a set of pieces that together tell a story, less through plot than through the poetic essences of events. One hopes that some day Medina’s work may be set to music, perhaps to jazz — the music that had been so crucial to Langston as a young writer, living in France, working as a dishwasher in a jazz club, listening to the music while he scrubbed, making up poems in his head to accompany it. There are biographical notes in the appendix of the book that provide the background to each of Medina’s verses, but what’s important in the end are the rhythms of a life, and the poems that can be made out of that life, poems that, like the oranges that Alice Walker brought to the dying Langston Hughes, are “a bag of sun.”