Edward Steichen

Listen to the Recess! Clip

| Author | John Cech |

| Air Date | 3/27/2000 |

Edward Steichen Transcript

Edward Steichen, one of America’s most noted photographers, was born today in 1879 in Luxembourg, where he spent the first two years of his life before his family resettled in Michigan and his father went to work in the copper mines of the Northern Penninsula. By the time he was in his teens, the family had moved down to Milwaukee where Steichen apprenticed in a printing company, and was soon involved organzing the Arts Students League in the city. By 1899, he had his first show of photographs–hazy, romantic pictures, not the rigidly posed portraits for the mantel piece or piano-top. By 1902, Steichen had managed to get to Paris to study painting, but within a few weeks, he’d given it up and was taking photographs again–this time of some of the emerging greats of modern art and literature that he had met–Gertrude Stein, Picasso, Rodin, Matisse, G. B. Shaw, Isadora Duncan. These shadowy, revealing portraits soon made him famous and wealthy, and, in one friend’s phrase, “majestically confident.” He was brave enough to tweak the formidable J. P. Morgan during a sitting, and then to snap the shutter and catch the great financeer glowering, clutching the arm of his chair, the light glistening on the wood, turning it into the blade of a knife.

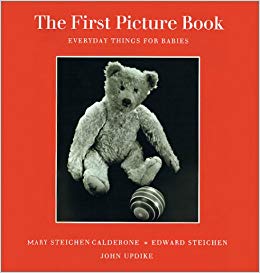

In 1930, Steichen and his daughter, Mary, an educator, teamed up on a series of photography books for young children that were part of the movement in preschool education that stressed the “here and now” and everyday rather than encouraging fantasy. Their first book was called, simply, The First Picture Book–Mary provided the conceptual framework and introduction to her father’s photos. The book focused on the things in a child’s immediate life–beautiful, stark, straight-ahead photos of familiar objects, seen without haze or shadowy abstractness–a glass and toothbrush, a sink, a teddy bear, a plate and a cup of milk, blocks, a wagon, a chair. The book was wordless and was meant to encourage interaction between toddlers and parents. The next book, which came out a year later, in 1931, and was meant for three-year-olds, showed children interacting with the toys and other objects of their daily life. Again it was without words, thus encouraging children, as Mary states in her preface, to make up their own stories to accompany it, so that they develop their powers of articulation. What a refreshing thought. And what a moment in the history of art for young people, when the genius who produced those magnificent photographs of the Flat Iron Building and those incredible heavy roses of Voulangis would also make photos of a child’s brush and comb, and a plate of bread and butter.