Children’s Literature from Poland

Listen to the Recess! Clip

| Author | Kevin Shortsleeve |

| Air Date | 1/29/2003 |

Children’s Literature from Poland Transcript

The history of Poland, as well as the history of Polish children’s books, has long been influenced by its un-enviable geographic location between the rising and falling superpowers of Prussia, Russia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Nazi Germany and most recently, The Soviet Union.

In response to this problem of setting, perhaps, Polish children’s literature and folk tales have long been attracted to themes of liberty and defiance. Polish folk collections such as W. S. Kuniczak’s [Ku-nish-chak’s] The Glass Mountain, are filled with magical kingdoms, enchanted castles, witches on broomsticks, and most interestingly — like in a painting by Marc Chagal — a preponderance of objects or persons who have the ability to fly. These are tales of broad wit and sly allegory that stand in defiance to oppression and injustice, and, in their many-literal flights of fancy, speak indirectly of freedom.

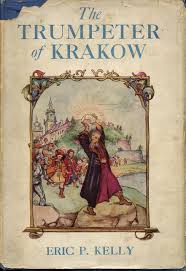

In the 1800s, when Polish children’s books were first emerging, Poland was situated between the two super powers of Prussia and Russia. Subjugated under these vying military powerhouses, Polish language books were banned from schools. In reaction against this edict, the author Klementyna Tanks published The Journal of Countess Francoise Krasinka that told of Polish life and manners before subjugation by Russia and Prussia. Tanks’ book, then, encouraged an awareness of the very same Polish traditions that their oppressors wished to erase from memory. Preservation of the Polish language and Polish cultural traditions has remained an issue throughout the invasions by the totalitarian regimes of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. But even before these incursions, certain Polish legends found their way into western popular culture, including Eric Kelly’s 1928 children’s novel, The Trumpeter of Krakow, which won the 1929 Newbery Award. The original legend of The Trumpeter of Krakow is a tale of defiance and bravery in the face of an invading army of Tartars. And The Trumpeter’s symbolism was not lost on the broadcasters of Radio Free Europe, who began their broadcasts in Polish with the Trumpeter’s call to arms. Kelly’s novel may not follow this legend precisely, but it stays true to its original spirit in its call to the young hero in the book to bravely help defend his father.

While children’s books in Poland today are enriched by inspired poetry and exquisite artwork, they are enhanced, at the same time, by a body of literature that always, above all other concerns, fought for the lost liberties of an often oppressed and now, happily, free nation.